Let’s take Melbourne for example.

The Victoria capital had over 90,000 new property listings in 2023. However, CoreLogic data showed there were only 81,203 dwelling sales in the same period which indicates an oversupply.

As a result, Melbourne’s home values declined to 0.9% in the three months to January and 0.1% annually.

“In this sense, the market was indeed oversupplied in 2023, which caused purchasing values to come down slightly,” CoreLogic head of research Eliza Owen said.

“Demand for housing in Melbourne is seemingly sluggish and listings are accumulating, while at the same time, the political discourse about the critical undersupply of housing is louder than ever.”

Recent data suggests this trend will spill over through 2024.

Earlier this week, SQM Research revealed total property listings – which include properties listed for less than 30 days and over 180 days – in Melbourne as of January went up 6.2% year-on-year.

More notably, the investment research firm found more sellers in Victoria were increasingly desperate to sell their homes under distressed conditions, with activity under this segment rising 17.8%.

Distressed listings are typically sold at below market value as vendors tend to accelerate the sale timeline of the property. These include mortgagee-in-possession properties, deceased estates, and anything that indicates a must-sell situation.

Despite this, in 2023 property prices nationally clawed back all of their 2022 losses and then some to reach a new record high, while owner occupier loan sizes also hit an all time high.

Difference between market demand and market desire

The current status in Melbourne, according to Ms Owen, reflects the disparity between the market's fundamental demand and their actual capacity and desire.

“Terms like 'supply and demand' may be conflated across the two conversations, but they can be distinct from each other,” she said.

While there may be adequate supply to meet the demand, the market's desire to purchase – which is shaped by credit conditions and consumer confidence, among other factors – impacts their capacity to buy as well as influences their decision if they will indeed satisfy their need.

“Whether or not housing looks attractive to buy as an asset is different to needing somewhere to live,” Ms Owen noted.

It is very apparent in Melbourne, where various data point to increased housing demand.

In 2023, its population has increased markedly, its vacancy rates plunged below 1% while rents soared 10.7%, and it posted a 4.7% increase in new housing applicants resulting from homelessness in the year to June.

More Aussies opt to rent

It appears more Aussies prefer to rent even if high prices lead to rental stress.

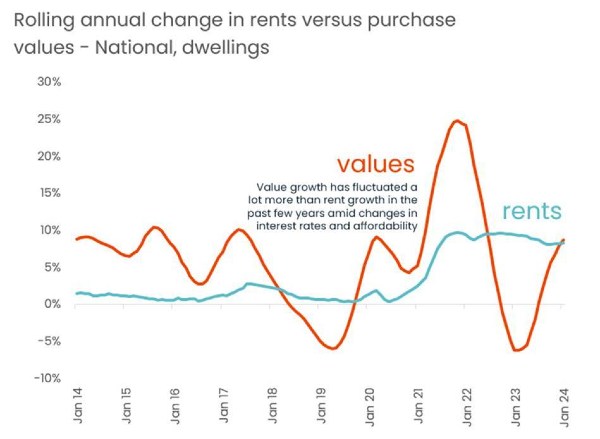

The disparity in changes between home values and rent prices – where the former has fluctuated amid changes in policy settings while the latter moved consistently higher – is a good indicator of the market’s housing preference, according to Ms Owen.

Data source: CoreLogic

“The private rental market values can be a pretty good proxy for the more fundamental need for housing, because the private rental market is the most common fallback for people who cannot, or are not willing, to buy housing,” she said.

CoreLogic’s latest Housing Chart Pack showed home values have gone up and down while rent prices have increased more than 8% in the past three years.

The report found rent values have had three strong years of consecutive increases, against mixed capital growth performance.

Nationally, Australian rent values increased 8.3% in 2023, while the annual growth in rents has accelerated slightly, from the 8.1% increase recorded in the 12 months to October.

The value of residential real estate was estimated to reach $10.3 trillion at the end of December, however, the growth trajectory for housing values across the combined capitals has broadly slowed since late May.

Sales across the country in 2023 were 2.8% lower than the previous year, and the median time it takes to sell a capital city home moved slightly higher to 29 days in December.

The evident disconnect between strong fundamental demand and low purchasing demand shows buyers remain particularly sensitive to changes in interest rates and other aspects that make it easier to transition from renting to owning.

“For example, a reduction in mortgage rates, or the serviceability assessment buffer, would increase borrowing capacity for lower-income households, boosting the number of buyers in the market,” Ms Owen said.

“Value falls in the Melbourne market will also start to flatten out once prices are low enough to entice buyers.”

Though the RBA has decided to keep the cash rate unchanged at 4.35% in February, which industry experts expect to help stabilise the housing market, Ms Owen maintained her stance that enough social housing will yield better results in alleviating the crisis.

“It helps to avoid conflating a decline in dwelling values as a step toward solving the housing crisis, and acknowledging that some households will never be in the market to buy," Ms Owen said.

“In these cases, it is important to have a consistent supply of social housing outside of market fluctuations, to ensure adequate housing for those that just need somewhere to live.”

Photo by Pavel Danilyuk on Pexels